| Mike, Pam, Penny, and Father |

In The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison explores the dynamic between white standards of beauty, womanhood, home life, and family and the realities of her characters. She uses the classic Dick and Jane primers as a visual of those white standards: two heterosexual, middle-class parents and three very blonde children who are always clean and well-dressed. This family experiences only minor interpersonal conflicts, and the children have lives that are defined by safety and playtime. The mother stays at home and cares for the children, while the father works outside the home and returns at dinnertime and on weekends. These children do not know hunger, or cold, or pain, or fear. Morrison contrasts this with the lives of her characters, who view these storybooks as “how life is supposed to be” even though their experiences are nothing like those of Dick, Jane, and Baby.

So many young children of color learned to read with Dick and Jane primers, but these books did more than just teach children how to read. They also worked as cultural primers, exemplifying a white culture that all children should adopt as they grew. Children of color did not see depictions of themselves or their experiences in textbooks until schools began to desegregate in 1965 (Teach, 2021). That year, Dick and Jane readers were introduced to Mike, Pam, Penny, and their parents, who lived in the city, rather than the suburbs. While children could finally see dark-skinned children in their readers, these children’s lives were no different from those of Dick and Jane. Their clothing was the same, representing white standards of dress. Their parents represented the same traditional gender roles, and so did the children: Mike lived up to the same standards for young boys, while Penny and Pam lived up to different standards as young girls.

Therefore, while Mike, Pam, and Penny may have had dark skin, they were still culturally white children living white lives.

|

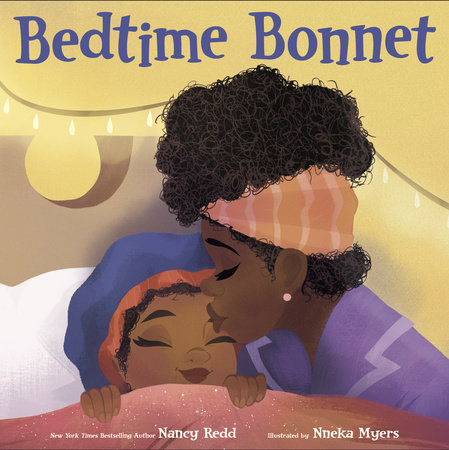

| Authentic Black representation in children's literature. |

Today, we are more likely to see representation of other types of families in children's media. However, many of these books are increasingly being targeted by book bans. According to Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman in Time, 88% of the faces that children see depicted in children's books are white, and she found that "even books designed to promote diversity still featured over 50% white faces and famous figures." (2023) So, while we may have made progress toward featuring images of diversity in children's literature, we still have a lot of work today. Black, indigenous, and Latinx children must be able to see images of themselves and their experiences in children's books and media in order to overcome the dominance of white cultural standards.

"Black children’s books offer young readers the chance to examine the past, question the present, and ponder future actions through affirming stories of exhilaration and triumph. As cultural artifacts, children’s books present models through which readers can come to understand themselves and the world in which they live." (Opoku-Agyeman, 2023)

Comments

Post a Comment